Insulin resistance

Insulin resistance

Insulin resistance is defined clinically as the inability of a known quantity of exogenous or endogenous insulin to increase glucose uptake and utilization in an individual as much as it does in a normal population. Insulin action is the consequence of insulin binding to its plasma membrane receptor and is transmitted through the cell by a series of protein-protein interactions. Two major cascades of protein-protein interactions mediate intracellular insulin action: one pathway is involved in regulating intermediary metabolism and the other plays a role in controlling growth processes and mitoses. The regulation of these two distinct pathways can be dissociated.

Signaling Pathways:

Several mechanisms have been proposed as possible causes underlying the development of insulin resistance and the insulin resistance syndrome. These include:(1) genetic abnormalities of one or more proteins of the insulin action cascade (2) fetal malnutrition (3) increases in visceral adiposity. Insulin resistance occurs as part of a cluster of cardiovascular-metabolic abnormalities commonly referred to as "The Insulin Resistance Syndrome" or "The Metabolic Syndrome". This cluster of abnormalities may lead to the development of type 2 diabetes, accelerated atherosclerosis, hypertension or polycystic ovarian syndrome depending on the genetic background of the individual developing the insulin resistance.

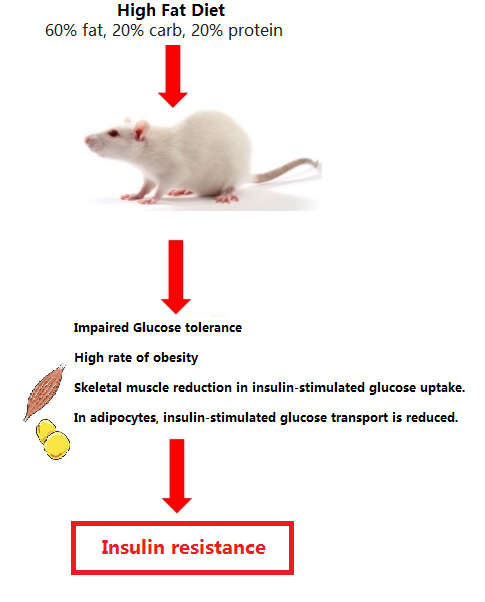

Induction of Insulin resistance:

The most commonly used rodent models of obesity and the metabolic syndrome are either monogenic or diet induced.

Monogenic models of obesity, such as rodents with a defect in leptin production (ob/ob mice) or its receptor

High-fat diets (HFD) with relative fat fractions varying from between 45 and 60%, with fat. HFD: (60% fat, 20% carb, 20% protein) for between 4 to 16 week.